Geothermal borefields can be used in many different scenarios, but one general distinction is between individual and collective geothermal systems. In this article we will discuss three different types of geothermal systems, from fully individual to fully collective, and give you some insights into when one could be a better choice than the other.

Three types of geothermal borefield systems

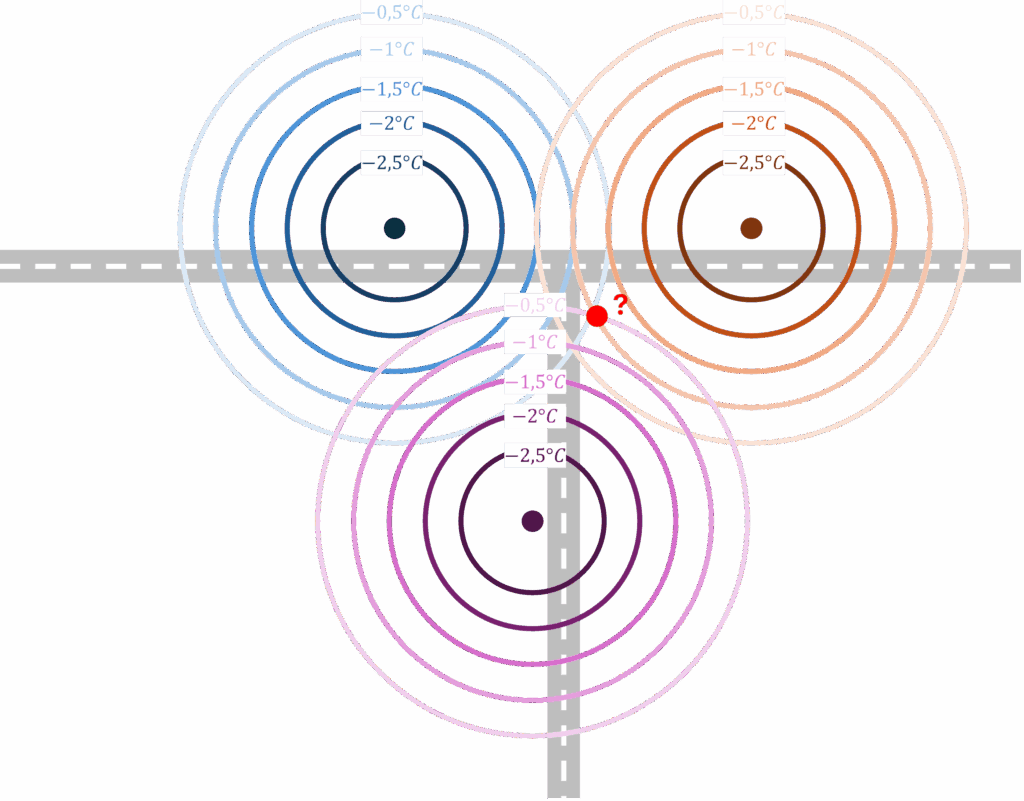

Whenever you have a project with different units or buildings, such as a newly built neighbourhood or an apartment building that you want to provide with geothermal heating and cooling, you are faced with a question: do we install a collective or an individual system? In the image below, three general types of solutions are shown.

On the one hand, shown on the left, there is the fully individual solution. Each apartment, building or unit has its own production of heating and cooling (i.e. a ground source heat pump) and is connected to its own separate borehole or borefield.

On the other hand, shown on the right, there is the fully collective solution. Here you centralise your heating and cooling production and distribute the heat and cold to the different buildings. When this is done between multiple separate buildings, the solution becomes a traditional heating and cooling network.

The last option, which has gained a lot of attention lately, is to work with individual production units for heating and cooling that are connected to a centralised borefield. This solution is similar to what is called fifth generation district heating, where the geothermal temperatures are shared among different users who can decide themselves how to use it for heating or cooling.

All three of the options above have their own use cases, advantages and disadvantages. In the following sections we will discuss them one by one, focusing on the geothermal design aspects (peak power and imbalance) as well as general concerns (cost, maintenance and societal effects).

!Hinweis

In this article we will not discuss the benefits of using a collective geothermal system over individual air source heat pumps. The advantages of geothermal borefields were already discussed in another article.

Individual production, individual borefield

When all your buildings or units have their own separate heating and cooling system, you need to make sure that each individual borehole (or borefield, depending on the size of the building) can deliver 100% of the peak load of the building. In addition, each geothermal source should also handle 100% of the imbalance. The combination of these effects can put quite a lot of pressure on the design of the individual borefields.

However, it could be that in this situation the average borehole to borehole spacing is larger than in a traditional borefield. Imagine, for example, that you have a neighbourhood where each individual house has its own geothermal borehole or boreholes. Typically, these boreholes would be further apart than if they were centralised in a single field. Having a larger borehole spacing could help to cope with the potential imbalance, as we discussed a couple of weeks ago in this article.

Nevertheless, the fact that your borefields are connected to individual installations does not mean that they are completely separate from each other. Between any pair of geothermal borefields, there is always a certain degree of thermal interference.

Interference

Interference describes the effect that neighbouring borefields have on one another, since the thermal influence does not stop at the edge of the borehole or property. This interference is caused by the imbalance of a certain system, which will cool down or heat up the neighbouring ground year after year. The closer the individual boreholes are, the greater this geothermal interference will be. It goes without saying that we need to take this effect into account when designing individual borehole systems.

!Hinweis

In GHEtool Cloud, it is possible to simulate this thermal interference between neighbouring systems. You can find more information about this in our article hier.

In the example below, the importance of this interference becomes clear. Imagine we have nine individual houses, each with its own geothermal borehole. If we were to design the borefield for a single house in isolation, we might end up with a system that, after 20 years, has a minimum average fluid temperature of 0.41°C. However, if we take the same design and simulate it for the entire neighbourhood together, the final temperature (due to interference) becomes -0.88°C.

It should be clear that individual boreholes need to be designed with interference in mind.

!Hinweis

In the case of our nine houses, not every geothermal borefield experiences the same level of geothermal interference. The boreholes located in the centre of the neighbourhood will experience more interference from the surrounding systems than those on the edge of the project. Therefore, simply increasing the design of all houses by the same amount would lead to an overestimation of the required borehole length for some buildings, while others might experience a slight undersizing. It is best to simulate these situations directly with the interference module in GHEtool Cloud todetermine the specific influence on each system.

Fazit

In general, we can say that the final borefield size, when working with fully individual systems, is governed by two major factors:

- A higher resulting peak power (100% of the building demand)

- A lower influence of imbalance and interference, depending on the borehole to borehole spacing

The relative importance of these two effects can differ from project to project. Generally speaking, in apartment buildings where the boreholes are relatively close together (as if they were a single borefield), individual systems will lead to slight oversizing. For neighbourhoods where the boreholes are further apart than they would be in a single borefield, the individual design could be slightly smaller.

With regard to maintenance costs, these are relatively high for this type of solution, since servicing multiple heat pumps leads to higher cumulative expenses. In addition, as every building has its own heating and cooling unit, this will result in higher electrical peak loads on the grid, requiring greater capacity.

Individual production, collective borefield

Another option is to keep the installations separate but connect them to a single borefield. This could be interesting in cases where the boreholes would in any case be close to each other (for example due to limited space, as in the case of an apartment building), or in the context of a fifth generation district heating network. Since we now have a collective borefield, we can identify two major benefits:

- We can work with one overall imbalance, which will always be equal to or smaller than the sum of the individual imbalances. Imagine, for example, that one building requires more heating than cooling while another has the opposite demand. The resulting borefield could then be more balanced, whereas in the case of individual solutions we would have to cope with the imbalance twice.

- We can work with a lower peak power due to simultaneity.

!Caution

When working with individual heat pumps, simultaneity becomes increasingly difficult to predict. Imagine, for example, domestic hot water profiles. Most people shower in the morning or in the evening, leading to a potentially high overlap in peak power. Furthermore, more and more heat pumps respond to dynamic electricity prices to determine when to heat or cool a building. Since all heat pumps follow the same electricity price profile, this could in extreme cases lead to synchronised operation with full simultaneity.

In this case, the boreholes are potentially closer together, leading to a stronger influence of imbalance. The positive side is that, since the imbalance is now centralised, we can also use regeneration (for example through a dry cooler, solar absorbers, and similar technologies) to address this issue. More information can be found in another article. However, the central borefield itself remains a passive component with no control system of its own. Adding regeneration would therefore require a centralised control strategy, which could increase the system’s complexity.

Fazit

When working with a collective borefield, you potentially have a lower peak power and imbalance to deal with. However, since the boreholes are closer to one another, the influence of the imbalance might be greater. The final decision on whether this is beneficial or not ultimately depends on the specific project. Generally speaking, for apartments where the boreholes are already quite close together, a collective borefield is likely to be cost efficient. For neighbourhoods, this is usually not the case, unless the boreholes can be placed further apart and connected through a fifth generation district heating network.

Since there are still multiple systems, the cumulative maintenance cost of this solution remains relatively high, as does the total peak power demand on the electricity grid. Because simultaneity cannot be guaranteed and regeneration is somewhat more complex in this case, the borefield is generally larger than in the following option.

Collective production, collective borefield

Our final option combines centralised heating and cooling production with a centralised borefield. This is the traditional district heating and cooling solution, with a shared production system. As in the previous case, where we centralised the borefield, we benefit from a lower overall imbalance compared to the individual systems.

However, in contrast to the collective borefield with individual production, having a centralised production system means that we can account for true simultaneity. This allows the heat pump to be sized differently, resulting in a lower peak power demand.

As in the previous option, the boreholes are likely to be closer together, which can increase the effect of imbalance. Nevertheless, since we also have a centralised production unit, it becomes relatively easy to mitigate this by creating a hybrid system or incorporating regeneration.

Fazit

Having a fully collective system will result in lower peak power demands on the borefield and a similar overall imbalance. Therefore, when compared to the case with individual production units and a collective borefield, this solution will generally lead to smaller geothermal systems, although it still depends on the specific project and borefield geometry. In general, this solution tends to be more cost efficient for apartments, while it may be more expensive for neighbourhoods due to the need for insulated distribution pipes for heating and cooling.

Since we now have only a single system to maintain, the cumulative maintenance cost is lower, and the required electrical capacity from the grid is also reduced. Collective systems are easier to optimise.

Simultaneity in the ground?

In the three different cases discussed above, we mentioned simultaneity (which you can read more about here), the concept that peak loads smooth out when multiple users share the same system. This explains why, in the case of a collective borefield, and especially for a fully collective system, there is a lower resulting peak power on the borefield. This is not the case, however, for individual systems.

“But there is interference between the different boreholes. Is there not simultaneity underground?” The short answer is no. For the long answer, we take a look at the graph below.

As mentioned, interference is real and very significant for neighbouring systems, but the time scale of interference and that of simultaneity are very different. Above, we revisit the long-term effects on borefield temperature (more information hier) for three different borehole spacings. As can be seen, all lines initially coincide, but after one to two months the case with a 6 m borehole spacing begins to diverge. This marks the moment when the heat has travelled far enough through the ground to reach the neighbouring borehole.

This time scale of months to years (depending on the distance) is much longer than the time scale at which simultaneity occurs, which is immediate. Therefore, interference is relevant for the long-term and for the collective imbalance of all systems, but it cannot be used to achieve lower peak power values.

Fazit

In this article we discussed three different geothermal solutions: the fully individual system (where both production and boreholes are separated), the fully collective system (with collective production and a shared borefield), and a combined solution, where separate production units for heating and cooling are connected to a central geothermal source.

Although the specific cost savings of moving from individual to collective systems depend on the characteristics of each project, moving towards a collective borefield offers the advantage of working with a combined imbalance rather than addressing it on a building by building basis. In addition, centralising production can help reduce maintenance costs, limit the peak power on the borefield, and lower the required electrical capacity.

Literaturverzeichnis

- Sehen Sie sich unsere Videoerklärung auf unserer YouTube-Seite an, indem Sie klicken hier.